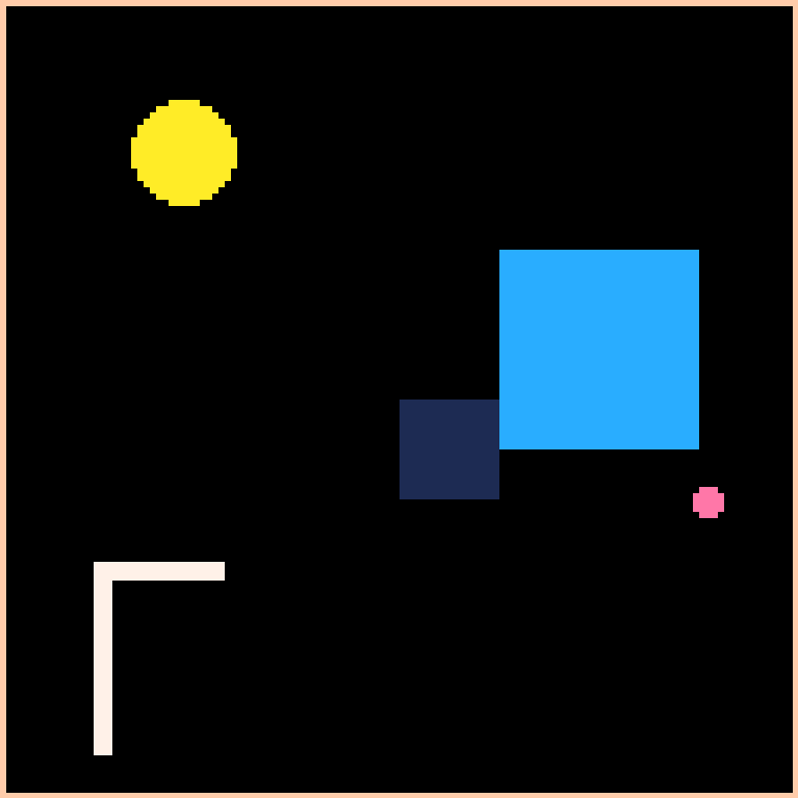

Music Box with 16 Tunes

Game Gallery

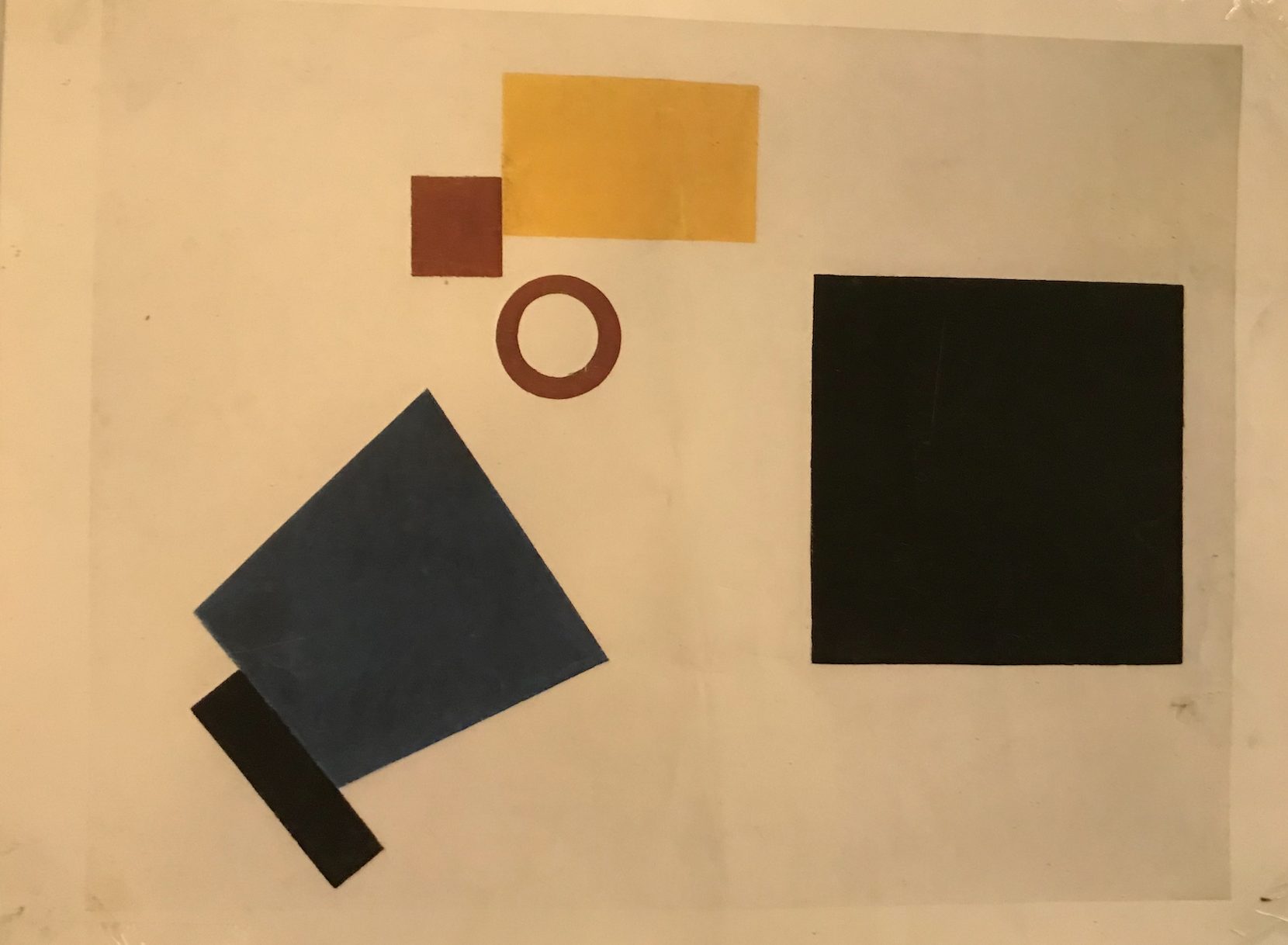

I made this game for the new media seminar that I took in the winter quarter 2021. I took inspiration from Kazimir Malevich’s work Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions. This work has been hung on the wall of my living room in many directions.

I was also thinking about works like Symphonie Diagonale (Viking Eggeling, 1924) while making this game, and planned to add some trails to the bouncing ball to create the movements of lines. But I was too occupied by my coursework around that time, so I decided to keep it as simple as it was.

After this game was done, I was really glad that I read some passages from Gilbert Simondon’s newly translated book Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information, where he talks about pendulums, the kinetic energy and the potential energy. I often find his writing confusing, but I do like this part very much. It shows us that the transformation of energy happens when something is oscillating between two states. I felt that there is something resonating between the game and the passage.

“We shall begin with this postulate: individuation requires a true relation, a relation that can only be given in a system state that envelops a potential. The consideration of potential energy is not merely useful insofar as it teaches us to think the reality of relation; it also offers us a possibility of measure through the method of reciprocal convertibility; for example, let’s consider a series of increasingly complicated pendulums, and let’s attempt to note the transformations of energy of which they are the source during a period of oscillation: we shall see that we can confirm not only the convertibility of potential energy into kinetic energy, then into potential energy, which is converted back into kinetic energy, but also the equivalence of two different forms of potential energy that are converted into one another through a determinate quantity of kinetic energy.” (57-58)

A reflection essay

I also wrote a reflection essay as part of this creative project. I cited some works since this was written for a graduate seminar. I attach it (with very minor revisions) here just because it was a fun process to write.

2021/02/17

One of the lingering questions that fascinate me when I make my own game is how to make sense of the relationship between code and perception. For me, the coding process can be divided into two parts. First, I wrote the basic functions in the code editor panel. These are basic mathematical and logical statements that allow me to draw the game map, generate movements, play sounds, and design object interactions. This part was relatively easy for me as the operation of Music Box does not involve a lot of functions. The second part is to change the variables in these functions, including the force that the player can exert on the object, friction, gravity, colors, shapes, and sounds, so this game can give off certain feelings based on some of my rough thoughts about what aesthetics I should aim for. This second part was a very difficult (but rewarding) step for me. I spent most of my time trying to figure out how to adjust these variables to modify these forms and to rearrange the game space and the ball’s movement, just to achieve better organization of experience and sensory perception. This process speaks a lot to what Patrick Jagoda says about the experimentality of games, or “the ways in which video games condition experience and modulate affect through…video game sensorium” (74).

I used Pico-8 to make this game. It is an engine that works very well to make low-res pixel games. As Pico-8 has some built-in functions that are essential for designing the game, I did get a certain sense of “decorrelation” as I do not exactly know where and how these built-in functions work. All I know is that they did do their work. After I made a change to the code (often in numbers), I ran the game to see how these sounds, images, and object movements reflect this change. But the processing is somehow hidden, invisible. Shane Denson has pointed out this imperceptibility associated with digital imaging. There is according to him a transition from the cinematic regime to “post-cinematic media regime,” in which “older relations—such as that between a human subject and a photographically fixed object—are dissolving, and new relations are being forged in the microtemporal intervals of algorithmic processing” (1). What characterizes this post-cinematic regime is what he calls “discorrelated images” generated by computation algorithms. These images are discorrelated from human subjectivity because there exists an interval of digital image processing that remains imperceptible to human perception. It is the correlation between the human perceiver and the perceptual phenomena, a relation that holds for the cinematic regime, that is called into question by these processed images. Although I am not entirely sure about Denson’s description of this historical transition among different media regimes, I like his emphasis on this modulating agency of algorithmic processing and its social, political and philosophical hold on us. There is something transformative in this technical processing, in the conversion between logical statements of the code and what is immediately sensible.

Davide Panagia also talks about how the technical operation of computational algorithms brings forth transformations in terms of perceptibility and ways of participation. The way he discusses the function of algorithms as the arrangement of “movement of energies in space and time” seems to be an interesting way to look at my game (2). Exerting a force to the ball to give it speed is the main way for the player to interact with the game object. When the ball collides with the wall, its kinetic energy gets transformed into the inverse direction. This collision also triggers the playing of one sound, depending on the location that the ball hits the wall. As one of the main things that I experimented with is to add physics to this game, I am also fascinated by the question of how energy gets distributed and transformed in the virtual space of games, where forces and movements have to be introduced. Unlike the physical reality, the reality of video games, in a way that is reminiscent of animation, entails different energetics. Gravity and friction still operate here, but on a very different level.

Instructions

Use the direction keys to control the pink ball to create beautiful tunes of your own (It may not be too beautiful, but that’s awesome)! Enjoy gravity, friction, and the rapid/slow bouncing effect!

There are moments when my math expressions for coding the movement fail–you’ll see what happens. So far I don’t want to fix it because I think it is a fun surprise. Press X to restart.

Please enter full screen to enjoy the game better :)

使用方向键来操纵粉红色的小球,创造属于自己的美妙音乐(可能也不是太美妙!但是不美也很好!)。请尽情享受重力、摩擦和飞速的(和缓慢的)弹跳吧!

有时我的数学表达式无法很好地编码球球的运动,你到时候会看到什么将会发生。 到目前为止,我还是不想修复这个问题。请把它当成有趣的惊喜吧。 按X键重新开始。

全屏幕感受游戏会更美好呢!

Play